AMH 4112.001 – The Atlantic World, 1400-1900

Daniel Gould (c.1625-1716), a recurring presence in the Pemberton Paper archive, spent his life dedicated to the Society of Friends in colonial America. His lengthy service to Quakerism and his community led to various positions of leadership and sent him through trials which tested his faith. His life was spent travelling all over the American colonies to preach the word of God and promote equality between Quakers and early Americans.

Gould was born in Rhode Island as the son of two English immigrants. He was conscious of the hardships that Quakers endured and ultimately became a victim of violence himself in a land where many sought religious freedoms. Profoundly struck by the reality of persecution in the New World as a Quaker, Gould became a voice for and chronicler of his denomination despite its risks. The literature he published is a narrative telling of the deep religious introspection which voiced social injustice towards the Quakers during his lifetime. 1

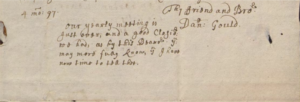

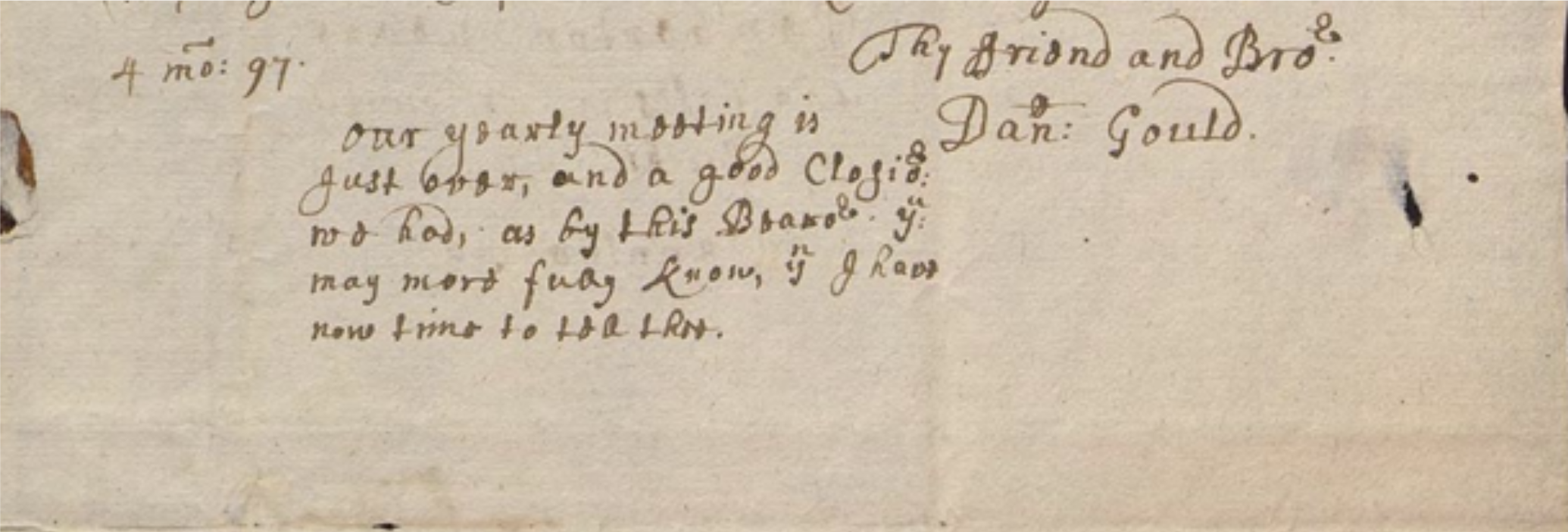

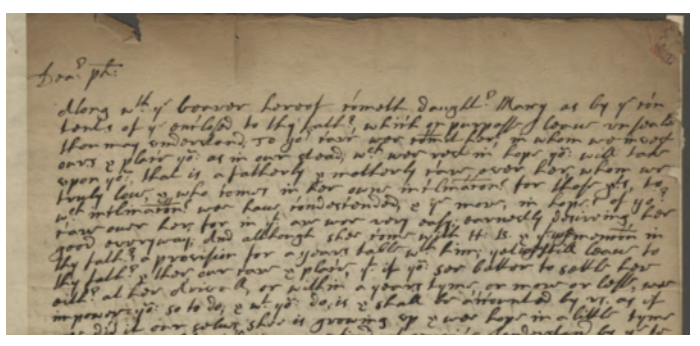

Gould, in his June 1697 letter to Phineas Pemberton, shows a deep connection to the Quaker and Pemberton family. This letter laments the loss of Phineas’ wife, Phebe. He details the fond memories he has of her from the first time they met in Maryland, and he recalls how happy they had all been together. This letter is especially touching, containing genuine advice to Phineas about remembering her love and keeping her memory alive. Gould seems to not have words for the pain he feels for Phineas’ loss. “I Cannot forget her [kindness], when I parted from her out of MaryLand, [taking] my journey [homewards]; neither can I forget our Last parting, [which] was at [your] ferry, in much tenderness & Love …Her love will never be extinct.” This exchange also mentions the Quakers’ meetings that created a more connected network and closer relationships within the Society of Friends. This letter notes that a meeting had just ended and Gould asks Phineas to pass along his well wishes to their mutual friends. 2

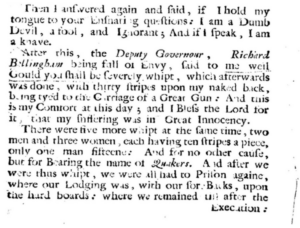

As a Quaker, Gould was determined to serve a purpose beyond himself through the publication of Quaker experiences. This determination eventually led him to be punished harshly in a New England that was intolerant of his denomination. Late in his life, Gould published a pamphlet where he discussed the execution of two Quakers, as well as his own personal trial and sentencing. A brief narration of the sufferings of the people called Quakers, who were put to death at Boston, in New-England tells a story in which he met a group of Quakers in the woods just outside of Salem, Massachusetts in 1659 to speak about God and the persecuted state of the Friends. They met in secrecy to avoid the law, but it found them, nonetheless. A Constable and “a rude company” confronted them, leading to a heated argument where all the Quakers were arrested and taken to jail in Boston.

After waiting several days for trial, Gould was stripped of his belongings, examined about many things pertaining to Quaker crimes, ridiculed and dehumanized, then sentenced to be tied to a “great gun” and whipped thirty times. 3 Fellow Quakers, Marmaduke Stevenson and William Robinson, were made an example after being picked out of the group and hanged for speaking blasphemy against Moses, God, and the civil government. 4 Gould recorded this graphic account as a testament to how poorly Quakers were treated in New England. He called the acts injustice because authorities never questioned those Quakers who were whipped and executed. Prosecutors never produced evidence against them and witnesses were either coerced into silence or never brought to testify. Gould took his jarring experience in the Boston jail as a reaffirmation of his faith. Thereafter, he spent most of his years as a traveling minister. He embarked on many voyages to Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Maryland (where he later met the Pembertons).5

Despite his hardships, Daniel Gould was dedicated to justice for Quakers and highlighting their struggles. Through mutual hardship and camaraderie, Gould found strength and support in his fellow Friends.